Oranges - Peeling Back The Science Behind Collagen

I don’t know about you, but when I take a sip of refreshing, tangy orange juice, I instantly feel happier. However, that joyful feeling isn’t the only thing oranges provide. When we eat oranges, we take in vitamin C, a nutrient that plays a major role in keeping our connective tissue healthy. Vitamin C is essential because it helps the body produce collagen, which supports youthful skin, resilient joints, and strong bones.

Vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid, is a water-soluble vitamin that humans can’t produce naturally, meaning it must be obtained through diet (National Institute of Health, 2021). Good sources of vitamin C include citrus, brussel sprouts, and guavas (Bubs Naturals, 2025). It is also available as a dietary supplement, but it is generally best to meet these nutritional needs through whole foods unless a healthcare professional advises otherwise (National Geographic, 2024)

Okay, okay. So what? Well, vitamin C is far from “just another nutrient.” It plays a critical role in collagen synthesis, which is essential for maintaining connective tissue. But what even is collagen? Let’s take a step back.

COLLAGEN AT A GLANCE

Collagen makes up about thirty percent of the proteins in your body. Since collagen supplements lack sufficient scientific evidence, diet is the best way to provide your body with the tools it needs to produce collagen on its own.

There are twenty-eight types of collagen, but Type I accounts for approximately ninety percent of all collagen in our bodies. Type I collagen is tightly packed together, and it is used to provide structure to bones, tendons, ligaments and skin (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). Its structure is a key component to the protein’s strength.

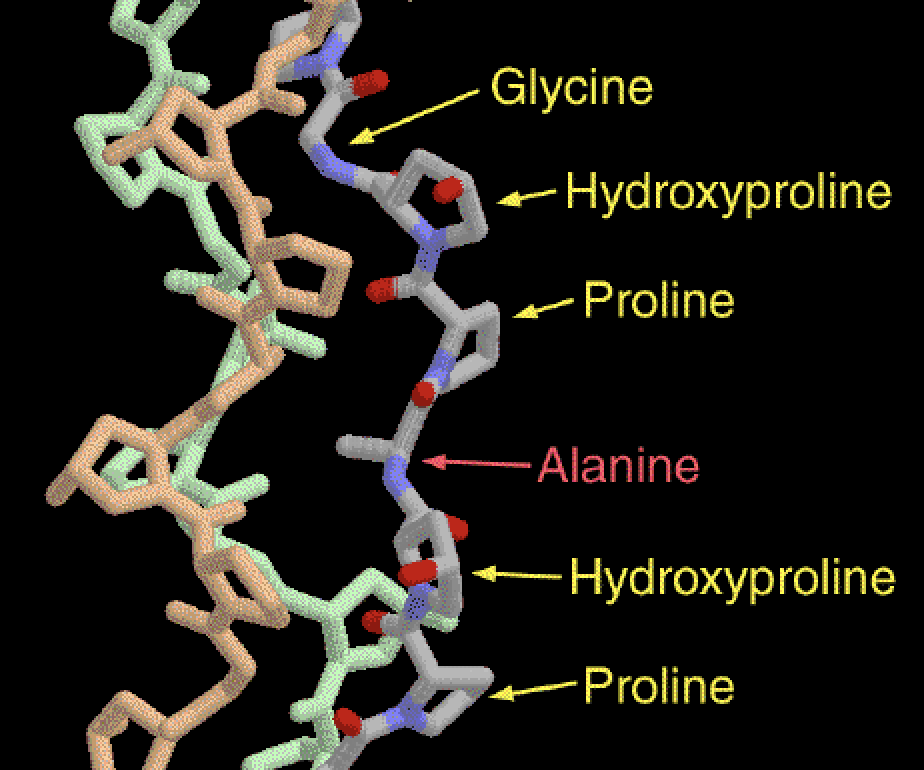

Collagen is primarily composed of three amino acids: glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline. Glycline is tiny and flexible, while proline and hydroxyproline are stiff and ring-shaped (Wu et al., 2023). These three molecules are arranged in a repeating pattern, which form an amino acid chain called a polypeptide. They repeat in this order:

Glycine → Proline → Hydroxyproline → Glycine → Proline → Hydroxyproline

Occasionally, there is another small amino acid known as “alanine,” but it is non-essential. (Alfa Chemistry, 2023).

Great. What makes this structure so special?

Well, typically, proteins fold into a tight spiral called an “alpha helix” which requires the amino acid chain to bend easily. However, the proline and hydroxyproline in collagen are too rigid, limiting the protein’s flexibility.

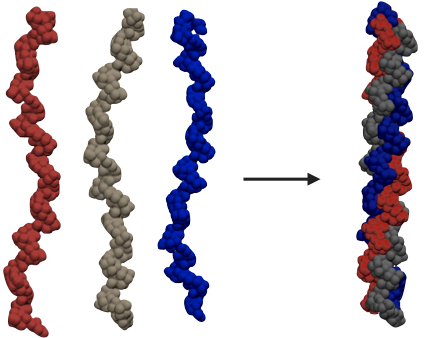

The stiffness of these amino acids limits collagen’s ability to twist tightly enough to form an alpha helix (Wu et al., 2023). Instead, it forms a “left-handed polyproline II-type helix” (Adzhubei & Sternberg, 1993). There’s a tongue twister for you.

Think of protein structures as locks of hair: An alpha helix forms tight coils, while left-handed polyproline II-type helices are more similar to loose, gentle waves. When three of these waves twist together, they form a triple helix called tropocollagen, similar to three strands of a rope twisted together (Adzhubei & Sternberg, 1993).

But get this– The tropocollagen can only form if the pattern is exactly the same for all three strands. If the pattern isn’t exact, the triple helix can’t form properly (Adzhubei & Sternberg, 1993). Why? Think about it this way:

Each of the strands represents a rope. One rope has a thick knot every three centimeters, the second has a thin knot every four centimeters and the third has medium-sized knots every five centimeters, you can’t tie them together neatly. Similarly, only perfectly repeating chains can twist together to make collagen strong and durable. In essence, the stiffness of the molecules in collagen create a specialized structure perfectly suited to keep our body healthy and resilient.

CONNECTIVE TISSUE

Its stiffness and strength make it an ideal framework for supporting connective tissue, which supports and links all bodily systems. Connective tissue is quite literally the glue that holds our bodies together. There are two main types of connective tissue: “connective tissue proper” and “specialized connective tissue.” Under the umbrella of “connective tissue proper” is “areolar connective tissue,” which is the padding that fills the spaces between the organs to protect them (Cleveland Clinic, 2025). Areolar tissue is the “tissue paper” of the body, pun intended.

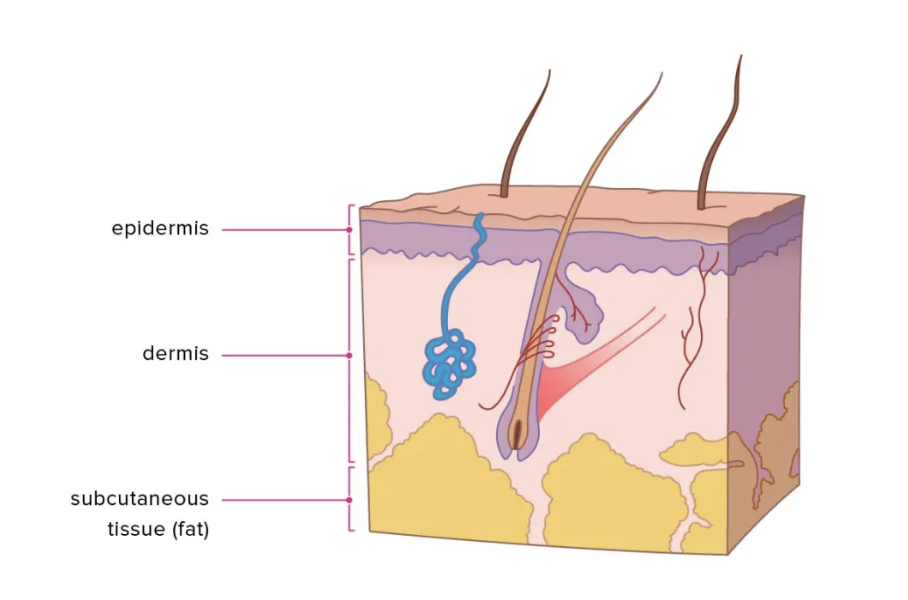

Under this same umbrella of “connective tissue proper” is “dense connective tissue.” It’s tougher, and it supports the body’s structure. Examples include the dermis, (thick, middle layer of skin) tendons, ligaments, and even the sclera, the white part of the eye. While collagen plays a role in both types of connective tissue, it mostly targets “dense connective tissue,” since these areas need to be resistant to stretching (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

BENEFITS OF COLLAGEN IN SKIN

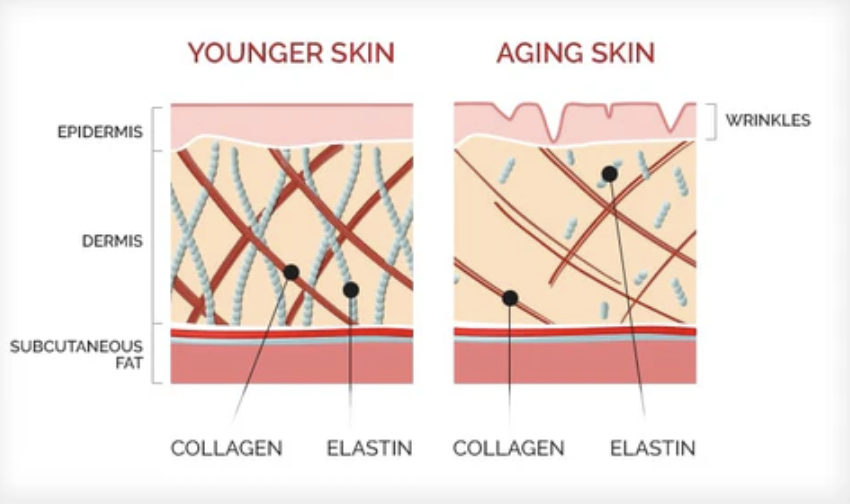

The dermis is a layer of connective tissue between subcutaneous tissue (fat), and the epidermis, the skin’s outermost layer that we touch. The dermis supports the outer layers of the skin and protects the deeper layers, known as the hypodermis (Brown & Krishnamurthy, 2022). Collagen, specifically type I and type III collagen are both prevalent in the dermis, and these fibers naturally arrange themselves in an orderly, crisscross formation in the extracellular matrix, which is just a fancy way of referring to the scaffolding of proteins that support specialized groups of tissues (Frantz et al., 2010).

That scaffolding is what keeps our skin from wrinkling and regulates the skin’s response to injury. Collagen is what keeps our skin healthy after getting a wound. How does it do this? The structural support provides a surface for new cells to grow on, like a trellis for vines. Without this structure, the new skin cells wouldn’t line up properly, and the wound wouldn’t close well (Mathew-Steiner et al., 2021).

But collagen can also be damaged by wounds. When you get a cut, collagen fibers in that area get partially broken down. But luckily for you, collagenase is on the job!

Think about your skin as a wall, and each collagen strand is a brick. If some bricks are cracked, you can’t just stack new ones on top– you must remove the broken ones and replace them. In the same way, unhealthy collagen is broken down by an enzyme called collagenase and rebuilt. So if you cut your skin, the damaged collagen fibers need to be removed before the body can produce new, healthy collagen to help heal the wound. Collagenase gently breaks down the old stuff without damaging healthy, surrounding collagen (Wang et al., 2024).

BENEFITS OF COLLAGEN IN BONES AND JOINTS

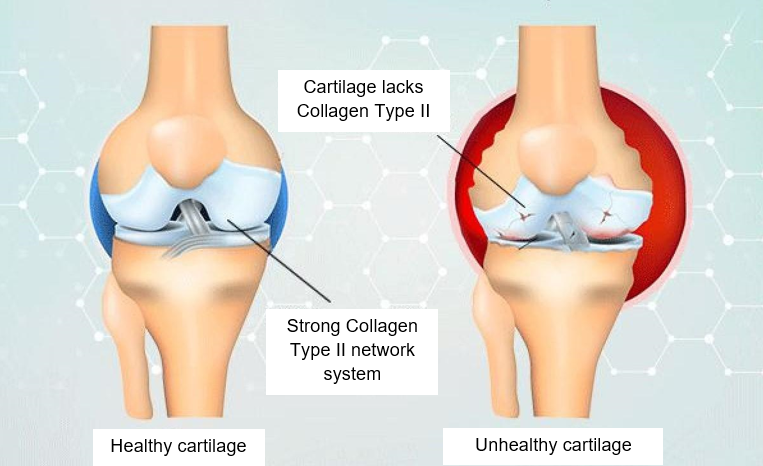

Joints and bones rely on collagen just like skin does. Bones are made of a hard matrix that is reinforced by type I collagen. Collagen gives bones strength, and a little bit of flexibility. Cartilage, the tissue that covers the ends of bones in a joint, is packed with type II collagen which provides a firm, but slightly flexible scaffolding that lets our joints move smoothly (DePhillipo et al., 2018).

In the joints, collagen holds everything together. Without strong collagen, cartilage can be worn down, bones become brittle, and joints lose stability. This is precisely what occurs in joint conditions like osteoarthritis (Ouyang et al., 2023).

When we put excessive pressure on the joints, collagen fibers in the cartilage can break. In the same way as skin, collagenase breaks down the damaged fibers so they can be replaced. This process keeps joints flexible and promotes strong bones. Without health, the “structural framework” would be weak, and movement would be painful or unstable (DePhillipo et al., 2018).

HOW DOES VITAMIN C PLAY A ROLE?

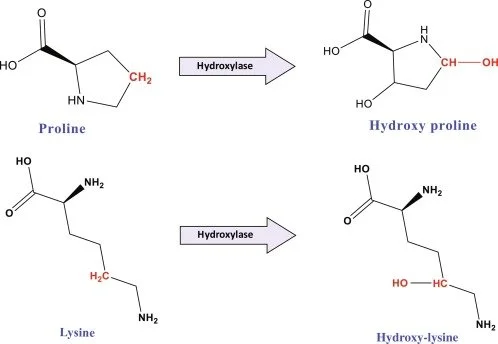

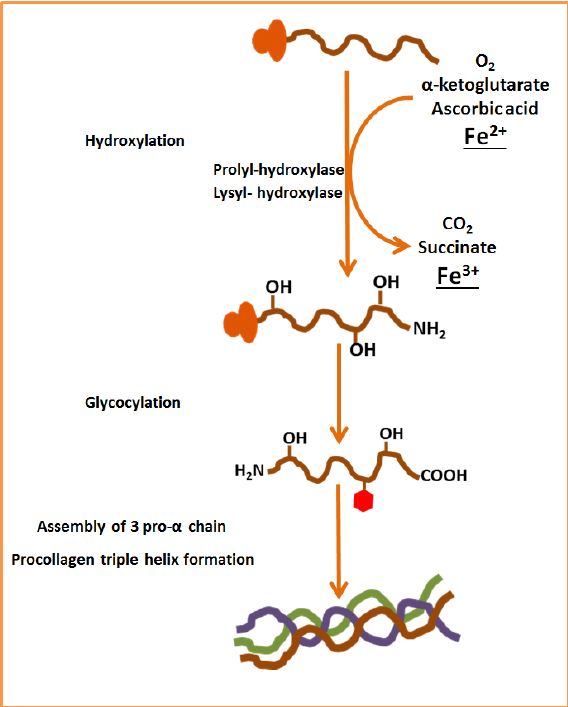

Vitamin C is absolutely crucial for collagen production, because it helps prevent inactivity in the enzymes that help create collagen. Collagen needs to undergo certain “chemical edits” to work properly. All proteins are made inside a cell, in an organelle known as the “rough endoplasmic reticulum.” When collagen is first produced, it isn’t functional yet. Amino acids proline and lysine must be chemically modified before the protein can leave the cell, and these modifications occur before the triple helix fully forms (Salo & Myllyharju, 2020). Three key enzymes are involved:

Prolyl 4-hydroxylases (P4Hs) → make 4-hydroxyproline

Prolyl 3-hydroxylases (P3Hs) → make 3-hydroxyproline

Lysyl hydroxylases (LHs) → make hydroxylysine

This process of chemical modification is called hydroxylation, in which a hydroxide (one oxygen and one hydrogen) is added to the molecule (Salo & Myllyharju, 2020). This process is critical, as the modified aminos stabilize the triple helix. They allow hydrogen bonds to form and allow for strong cross-linking later outside the cell (Jain et al., 2014). Without hydroxylation, collagen is unstable and doesn’t have the strength it needs to support our connective tissues (Tanveer Ali Dar & Laishram Rajendrakumar Singh, 2019).

Here’s where vitamin C comes in. The enzymes involved cannot function without Vitamin C. Great… but why not?

Here comes biochemistry with an answer! The enzymes contain iron in the Fe²⁺ form, and during the hydroxylation reaction, (when an OH group is added to proline or lysine), the iron in the enzyme is oxidized, meaning an electron is removed. This initiates a change, and Fe²⁺ becomes Fe³⁺, rendering the enzyme inactive until it is reset back to its intial state (Boyera et al., 1998).

I

n this case, oxidation inactivates the enzyme and prevents it from continuing its job. Vitamin C, or “ascorbic acid” acts as a reducing agent, benevolently donating an electron and changing Fe³⁺ back to Fe²⁺. This restoration allows the enzyme to continue catalyzing hydroxylation reactions.

Without sufficient vitamin C, the iron remains in the inactive Fe³⁺ state, hydroxylation stops, and collagen molecules remain unstable and weak (Kietzmann, 2023). Without sufficient vitamin C, your tissues become weak because hydroxylation cannot continue until the enzymes are reset (Maxfield et al., 2023).

While vitamin C supports collagen production at the molecular level, collagen levels in the body are also influenced by aging and environmental factors over time. As we age, collagen production inevitably drops. Elastin production (another protein that keeps the skin bouncy) also stops after puberty.

Collagen decline begins in the early twenties, and increases as we age. Without collagen providing structure, our epidermis begins to lose its structure, ultimately leading to wrinkles (Shek et al., 2024). As we age, we begin to experience more joint pain, since collagen is responsible for the strength of our cartilage, as well. In turn, our bones become weaker and brittle, which can cause osteoporosis or other conditions.

This decline can be exacerbated by smoking, pollution and excessive UV exposure. Being mindful of lifestyle choices and maintaining a diet rich in vitamin C helps support the body’s natural collagen-producing processes (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). So while orange juice may not be a miracle cure, it does supply the chemistry your body depends on to keep its connective tissues strong. Turns out, sometimes good science really does come with a bright, citrusy twist.

At the end of the day, collagen doesn’t care about skincare trends or the newest popular supplement– it cares about cold, hard, chemistry. So while oranges may not promise eternal youth, they do provide the vitamin that keeps collagen stable, skin healthy, and joints moving smoothly. Although orange juice doesn’t turn back time, it helps keep your body together, one electron donation at a time.